One of the most crucial areas of global development in artificial intelligence is the manufacturing and export of high-tech chips. In recent years, the intensifying competition between the United States and China has become increasingly significant, not only from a technological standpoint but also geopolitically. Recently, the U.S. government partially eased its previous restrictions on the export of NVIDIA’s H20 AI chips to China. While at first glance this may appear to be a loosening of the technological blockade, the reality is considerably more nuanced.

The authorization of H20 chip exports does not signal a return to full technological cooperation, but rather reflects a carefully calibrated compromise. The H20’s technological capabilities fall significantly short of those of the previously banned high-end H100 chips: its computational power is lower, memory bandwidth is reduced, and the interconnection capacity—critical for AI training—is also weaker. These technical differences are not accidental; they are intentional limitations.

Although Chinese tech companies may benefit in the short term from access to these chips, the situation poses longer-term risks to their pursuit of technological self-sufficiency—an essential condition for building a robust local ecosystem. For example, while the H20 may be suitable for running AI applications or smaller-scale inference tasks, training large language models—which demand immense computing power and high-speed data exchange—remains a serious challenge. Consequently, Chinese companies are effectively locked into the ecosystem of American manufacturers, primarily because NVIDIA’s CUDA platform remains more advanced and widely adopted than Huawei’s MindSpore framework.

This case vividly illustrates the complex interplay between market dynamics and political strategy. The loosening of export restrictions is driven by both commercial and strategic considerations. NVIDIA lost $2.5 billion in potential revenue in China in 2025 due to the export ban, while sales of the H20 chips already on the market generated $4.6 billion. These figures underscore the company’s substantial economic interest in maintaining a presence in China—even if that means selling less capable products.

During his recent visit to China, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang emphasized that global supply chains cannot simply be severed. China operates one of the world’s most extensive and intricate supply chain systems, which not only delivers components but also embodies significant innovation potential. According to Huang, international collaboration ensures the flexibility and efficiency of the global economy—even when such cooperation is narrowed or subject to new regulations.

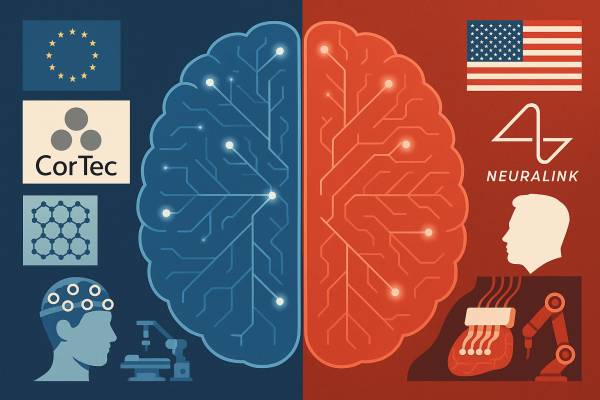

At the same time, companies like Huawei demonstrate that China is not merely a passive actor in the face of geopolitical and technological pressure. Huawei’s own Ascend 910B chip outperforms the H20 in several respects, particularly in AI training. However, migrating away from established platforms such as CUDA involves considerable financial and organizational costs, which many companies are reluctant to incur. As a result, while Huawei's technology may be competitive, it is likely to gain traction mainly among state-owned enterprises or in new projects built from scratch.

Meanwhile, the United States is seeking to extend its influence over chip technology by involving other regions, such as Southeast Asia. Malaysia, for example, recently introduced a new licensing requirement for the export, transit, and shipping of U.S.-made AI chips, which could further limit future shipments to China. This suggests that the goal is not complete decoupling, but rather controlled access: China may receive certain technologies, but not those that would enable the independent development of cutting-edge AI systems.

This dual-track logic is likely to continue shaping technological relations in the near future. The line between cooperation and competition remains fluid, but it has not disappeared. While China’s technological advancement continues, its pace and direction are increasingly shaped by external regulatory constraints. The U.S. strategy is not one of total isolation, but of guiding the contours of Chinese technological development according to its own strategic interests.

This approach is not without risks. In the long run, it may encourage China to accelerate its push for greater technological autonomy, an area where it still lags behind Western capabilities. As such, the coming years will likely be defined not only by technological breakthroughs, but also by ongoing tests of economic adaptation and diplomatic agility.